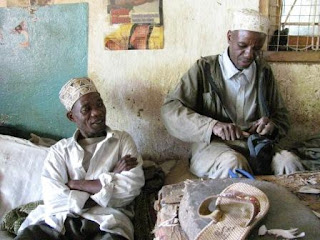

KILIMANJARO, TZ-- For Valentine's Day this year, I passed up the usual hot date and box of chocolates for a little hypothermia and the summit of Kilimanjaro--Africa's highest point. At 5:55 AM, after 3 days plus 5 hours of steady uphill slogging, I bagged Uhuru Peak with my travel buddy, David, and the world's best Kili guides, Rumisha and Nicas (pictured here).

KILIMANJARO, TZ-- For Valentine's Day this year, I passed up the usual hot date and box of chocolates for a little hypothermia and the summit of Kilimanjaro--Africa's highest point. At 5:55 AM, after 3 days plus 5 hours of steady uphill slogging, I bagged Uhuru Peak with my travel buddy, David, and the world's best Kili guides, Rumisha and Nicas (pictured here).As is often the case on this holiday, my exertions left me breathless. The air at 19,340 feet is quite thin, after all. But I was uncharacteristically frigid, despite my oh-so-sexy rig of silk long underwear, running tights, hiking pants, rain pants, three nylon shirts, fleece anorak, down jacket, Gore Tex shell, and face-flattering balaklava. Nevertheless, I was the second woman to peak that morning, having been among the last to leave Kibo Hut some 3 miles and 4140 feet below.

To watch the sunrise from the roof of Africa, about 50 climbers and our guides set out for the summit around midnight. The moon was so bright that we didn't need our headlamps. The Big Dipper hung strangely close to the horizon, rather than high above as it does in the northern hemisphere. The occasional shooting star whipped its sparkling red tail across the ink of the night.

The few glaciers that global warming hadn't yet eaten were pretty spectacular, too.

Despite the breathtaking beauty, I wasn't in it to win it. My hands had lost all feeling. My runny nose had cut a frozen stream across my face. My legs had grown cranky from the previous three days of constant ascent. I kept thinking about a friend-of-a-friend who died of high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) on Kili.

"Why am I here?" I thought. I recalled the mutterings of the schoolgirls who had followed me up a mountain on my bike just ten days earlier (see "All Ears" blog entry below): "These wazungu aren't going to give me any money. In fact, they're probably going to cut off my ears!"

I paused with Rumisha. "Sawa, sawa?" ("You okay?") he asked. I explained that my hands were frozen. He ripped my gloves off and wrapped my useless paws around a hot water bottle in his coat. He then gave me his mittens and took my flimsy gloves for himself. I was still thinking about phoning in my resignation when Rumisha kissed me on the cheek, grabbed my hand, and with a "Twende!" ("Let's go!") pulled me back on the trail.

When we reached the summit some two hours later, David and Nicas were already waiting. "Don't cry," Nicas said when I spied the peak marker. But he was too late--a sob had already forced itself out of my chest.

"How did you know that I was going to cry?" I later asked.

Nicas replied, "Tourists always cry when the reach the summit."

I still don't know what kinds of tears they were, though--of relief? of joy? of pain? Probably some combination.

The schlep back down to Kibo (3 miles) and then to Horombo (another 6.5 miles) was slick and quick.

(One more day of hiking took us the remaining 12 miles back to the Marangu Gate.) Upon my return I discovered that Kili had extracted only flesh wounds, including some abrasions around the cuffs of my boots and frost-burned lips, cheeks, and nose. I also learned that 10 of the people who had attempted to summit did not succeed--about average for the peak.

(One more day of hiking took us the remaining 12 miles back to the Marangu Gate.) Upon my return I discovered that Kili had extracted only flesh wounds, including some abrasions around the cuffs of my boots and frost-burned lips, cheeks, and nose. I also learned that 10 of the people who had attempted to summit did not succeed--about average for the peak.

A week later in Arusha, I bought a used copy of Jon Krakauer's Into Thin Air, a gripping account of altitude-addled decisions and death on Mt. Everest. Reading the book on the plane home, I realized that I had unwittingly snagged one of the seven summits--the highest peaks on each of the Earth's continents. Although I do not aspire to climb too many more of these overgrown hills, I must say that I'm a little proud of myself for hauling my Mississippi Delta-born, flatland-lubbin' backside up to one of the highest places on the planet.

NDUNGU, TZ--When I chose this bike tour, I blithely dismissed the caveat that the route was for advanced mountain bikers. "I ride on Mt. Tam all the time, and the Coastal Mountains, too," I told myself. Granted, on these rides I'm slicing my gazelle-like road bike along meticulously banked pavement. "But hey," I asked, "how much different could it be to muscle a fully loaded Sherman tank through steep corrugated trenches?"

NDUNGU, TZ--When I chose this bike tour, I blithely dismissed the caveat that the route was for advanced mountain bikers. "I ride on Mt. Tam all the time, and the Coastal Mountains, too," I told myself. Granted, on these rides I'm slicing my gazelle-like road bike along meticulously banked pavement. "But hey," I asked, "how much different could it be to muscle a fully loaded Sherman tank through steep corrugated trenches?"