MP, CA --I finally wrestled Flickr into submission and posted all of my Tanzania photos on my account. Alas, I haven't titled them yet. But you'll get the picture.

MP, CA --I finally wrestled Flickr into submission and posted all of my Tanzania photos on my account. Alas, I haven't titled them yet. But you'll get the picture.Most travel is better in the doing than in the sharing. But while sorting through the photographic evidence of my misspent February, I made a curious find: When it comes to safaris, the slide show beats the schlep. Indeed, the interplays of predator and prey, the landscapes soaked in beauty, the holy-cannoli-is-that-a-hippo-flipping? moments that I witnessed two months ago are astounding me now even more than before.

Ever the social scientist, I've named this phenomenon the safari sleeper effect.

Ever the social scientist, I've named this phenomenon the safari sleeper effect. I must admit: when I embarked upon my six-day safari to Tarangire, Serengeti, and Ngorongoro national parks--the durations and locales that all the guidebooks recommended--my baseline for amazement was abnormally elevated. I had just spent three weeks living by my spinal cord, as Vonnegut wrote, crashing along on my bike and hoofing up mountains, inhaling every pixel of this hypersaturated world. Somehow breathing dust in a Land Cruiser for six days with David--by now like family, for better and for worse--and two German tourists (though lovely people) just wasn't buttering my biscuits.

"The soft life," David calls it, this sitting still in a metal box and feeding on carbs four times a day. One starts to feel like a veal calf. And indeed, after weeks of dodging my own pointy hipbones--which exertion had exposed like storms unearth fossils--I felt the familiar layer of fat finding its way home.

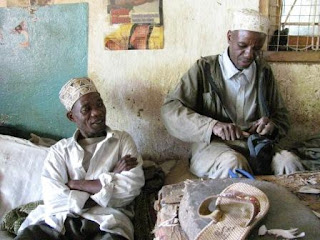

"The soft life," David calls it, this sitting still in a metal box and feeding on carbs four times a day. One starts to feel like a veal calf. And indeed, after weeks of dodging my own pointy hipbones--which exertion had exposed like storms unearth fossils--I felt the familiar layer of fat finding its way home.I also objected to whatever economic forces had sucked all the black people out of the national parks. After so many days of being one half of the white population in town, I was dismayed to realize that the majority of visitors to Tanzania--rounding the safari circuit in their identical khaki kits, replete with Tulley hat--most likely depart with the impression that Tanzania is a majority-white country. "Whitey is everywhere," I would say in Kiswahil to our guides, who always laughed at my small subversion.

But when I got home and snapped open my camera, I was finally and properly wowed. "Yeah, I guess watching those two cheetahs hunt from the termite mound was pretty rad," I thought.

"The pachyderms making an elephant's breakfast out of that grove was tres fab, too," I conceded.

The wildebeests feeding their calves warmed the cockles of my heart all the more stateside.

The goofy lionesses sunning their bellies raised a more seismic chuckle...

..as did the giraffe nibbling the clouds.

The zebras weren't just standing there; they divided the plain from the sky.

And I was, and continue to be, all the more grateful, every day, that sometimes the world or this life cracks itself open and lets me peek in.

Menlo Park, CA -- I'm back stateside and awash in more than 1000 photographs, which I'm slowly uploading to

Menlo Park, CA -- I'm back stateside and awash in more than 1000 photographs, which I'm slowly uploading to

NDUNGU, TZ--When I chose this bike tour, I blithely dismissed the caveat that the route was for advanced mountain bikers. "I ride on Mt. Tam all the time, and the Coastal Mountains, too," I told myself. Granted, on these rides I'm slicing my gazelle-like road bike along meticulously banked pavement. "But hey," I asked, "how much different could it be to muscle a fully loaded Sherman tank through steep corrugated trenches?"

NDUNGU, TZ--When I chose this bike tour, I blithely dismissed the caveat that the route was for advanced mountain bikers. "I ride on Mt. Tam all the time, and the Coastal Mountains, too," I told myself. Granted, on these rides I'm slicing my gazelle-like road bike along meticulously banked pavement. "But hey," I asked, "how much different could it be to muscle a fully loaded Sherman tank through steep corrugated trenches?"